By Howie Mooney

As morning broke on July 18, 1989, the Montreal Expos were sitting on top of the National League East Division. They held a 3 ½ game lead on the Chicago Cubs with a record of 53-39 after a 5-2 win over the NL West cellar-dwelling Atlanta Braves the night before. Expos’ shortstop Hubie Brooks played with a sore knee that he had hyperextended earlier in the season, and he went 0-for-3 in the game.

Brooks didn’t play the next night as his club dropped a 7-6 decision to Atlanta. After the game though, he was told that there was a call for him. He went over to the phone in the clubhouse and picked it up. His mother was calling from Los Angeles. She had news she wanted to tell Hubie before he heard it from anyone else. That day, his cousin and one of his closest confidants, Donnie Moore, had shot himself and committed suicide after trying to kill his wife, Tonya.

Moore had pitched in the major leagues for thirteen seasons and was two-and-a-half years older than Brooks and had always acted like a big brother to Hubie. Brooks made his big-league debut with the New York Mets at the end of the 1980 campaign. Moore pitched his first games for the Cubs in 1975. The news hit Brooks hard. According to his Montreal teammate, Wallace Johnson, the only words he said following the phone call were “Donnie is dead.”

* * *

Donnie Ray Moore was born in Lubbock, Texas on February 13, 1954, and his baseball journey took him to Paris, Texas and Paris Junior College and Ranger College in Ranger, Texas before he was drafted by the Chicago Cubs in 1973. He worked his way through the minor leagues and on September 14, 1975, at the age of 21, he got into his first Cubs’ game in a relief appearance.

Four evenings later, he made his first ever start against the Mets. When he left in the sixth inning, Chicago had a lead. But Darold Knowles gave up four runs through the eighth and ninth innings and the Mets ended up winning 7-5. He finished September with four appearances, with one of those being a start.

Through his career, he was mostly used out of the bullpen. From the time he entered the majors in 1975 until his final game in 1988, he made four starts and all of those were single games in each of his first four years. He spent a lot of that time working in middle relief, but things began to change in his last year in Atlanta in 1984. Or, more correctly, in 1983. He began to work on a splitter to go with his slider and other breaking stuff.

In that 1983 season, he began to be depended on to finish games a lot more. Those Braves were a decent team, finishing that year with a record of 88-74 in second place in the NL West. Moore made 43 appearances and finished 16 games, accumulating six saves. Those were all career highs for the righthander. He improved on those figures the following year. In 47 games in 1984, he was the last Braves’ pitcher in 29 of them and finished the season with 16 saves and a career low earned run average of 2.94.

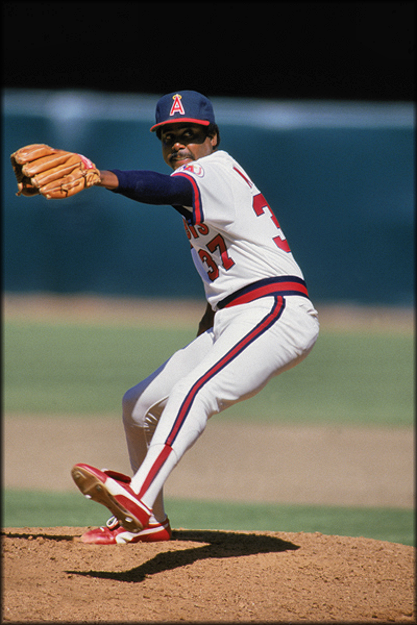

Before spring training in 1985, the California Angels had a couple of free agent compensation picks, and they plucked Moore away from the Cubs. The Angels had finished 1984 at 81-81, but that was good enough for second place in the AL West. Their timing in acquiring the soon-to-be 31-year-old reliever could not have been better. And they used him as often as they could.

For the first time in his career, Moore came to be viewed as an elite closer. He entered 65 games and picked up 31 saves. He won eight and lost eight and he posted a 1.92 ERA. 1985 was the only All-Star year in his thirteen seasons. He had refined his split-finger fastball, and it was now first rate. The Angels won 90 games that year. The only problem was that the Kansas City Royals were a game better.

And the Royals had a storybook ride as they faced the Toronto Blue Jays in the League Championship Series. 1985 was the first year that saw the LCS as a best-of-seven series. It had previously been a best-of-five affair. The Blue Jays jumped out to a 3-1 series lead in their first-ever attempt at an American League pennant.

But they couldn’t close it out and the Jays and their fans will never forget Jim Sundberg’s bases loaded triple in the top of the sixth inning of Game Seven to break the game open and send the Royals to the World Series. The Royals rode that wave as they knocked off the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games to take the World Series as well.

1985 saw the Angels improve but they still couldn’t get over that proverbial hump. That winter, six of the team’s players went to free agency. Of the six, Bobby Grich, Don Sutton and Moore all re-signed with the team. Juan Beniquez signed with the Baltimore Orioles. Al Holland joined the New York Yankees. And Rod Carew retired from the game.

The Angels exceeded their win totals from the previous year and exorcised their regular season demons by finally winning the AL West. Their opponents in that 1986 postseason were the Boston Red Sox. California looked good in the first game as Mike Witt bested Roger Clemens and the Angels drubbed the BoSox 9-1. But turnabout is fair play and in the second matchup, it was Bruce Hurst against Kirk McCaskill. Boston won it 9-2.

But, in Game Three, Moore posted the save as the Angels got past Dennis ‘Oil Can’ Boyd and his mates by a score of 5-3. John Candelaria got the decision in the victory. The fourth game went to extra innings, but it was the Angels who came out on top of a 4-3 result. They now held a commanding 3-1 series lead with the potential deciding game at Anaheim Stadium.

The Angels were managed by Gene Mauch. Mauch had made a few stops in his major league managing life. People like me remember him as the skipper of the expansion Montreal Expos. He was in that position from the beginning of the 1969 season until he was fired at the end of the 1975 campaign. Before that he was at the helm of the Philadelphia Phillies when they held a seemingly insurmountable 6 ½ game lead with twelve left atop the National League in 1964. Cue ‘The Phold’ and the Phillies snatched defeat from the jaws of victory as they lost that year’s pennant in feeble fashion.

In 1982, he was managing the Angels when his team held a 2-0 lead in the then-best-of-five ALCS over the Milwaukee Brewers. The Brew Crew, led by manager Harvey Kuenn, came back and ‘Harvey’s Wallbangers’ ended up going to the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals. Angels’ fans in 1986 were praying that the ghosts of Gene Mauch’s past would not come back to haunt this edition of the team.

In Game Five, the Red Sox took the lead as Jim Rice led off the visitors’ half of the second inning with a single. Two outs later, Rich Gedman lined a Mike Witt pitch over the right field fence for a two-run home run. Then Witt settled down and held Boston off the board for a while. Bruce Hurst was going for the Sox and for the first two innings he looked good.

But catcher Bob Boone was leading off the third for California. Boone worked the count against Hurst and was ahead at 3-and-1. Hurst had to come into the strike zone and Boone connected for a deep fly over the left field wall. The score stayed 2-1 for Boston as the teams headed into the bottom of the sixth.

Hurst had two outs in that inning and was ahead of Doug DeCinces with a no balls-two strikes count on him. But DeCinces pounded a Hurst mistake to the wall in right-centre field and wound up on second with a double. He was followed by Bobby Grich. Grich was behind 1-and-2, but he managed to catch a Hurst pitch and blast it over the wall in centre to give the Halos their first lead of the game at 3-2.

In the Boston half of the seventh, Witt allowed a two-out Gedman single but then got Dave Henderson to swing and miss on a 1-and-2 pitch to end the inning. Henderson had replaced Tony Armas defensively in centre field after Boston batted in the fifth.

The Angels came up in the bottom of the seventh. Bruce Hurst was no longer pitching. Bob Stanley came out to face California for this inning. The first man he saw was George Hendrick. He fired two quick strikes before Hendrick fouled off the third pitch. Then Hendrick squibbed a ball down the third base line that allowed him to reach base. Mauch then asked Boone to bunt Hendrick over. The catcher executed the sacrifice, and the Angels had a man in scoring position.

Gary Pettis then worked the count full before earning a base on balls. That brought Rob Wilfong to the plate. He hit a Stanley pitch to the wall for a double. Hendrick scored, Pettis went to third and when the dust cleared, Wilfong was standing on second. Next man up was Dick Schofield and Stanley walked him intentionally to load the bases. There was still only one out.

Stanley missed the zone on his first two pitches to Brian Downing. The next pitch Downing saw, he lofted a fly ball to centre field. It was deep enough to bring Pettis home easily. The Angels were up 5-2 now. That was how the inning ended. Angel fans were feeling quite enthused at this moment. Their team held a three-run lead after seven innings and their ace, Witt, was looking very comfortable.

Witt did allow a leadoff single to Mike Greenwell to start the eighth. But then he got Wade Boggs to hit into a 6-4-3 double play. Marty Barrett was the next Boston batter and Witt induced him into popping up to Wilfong at second to finish off the inning. The Angels’ ace used just nine pitches to get the Red Sox out in the eighth. The Angels were on the verge of getting to their first ever World Series.

Stanley got the Angels out in the bottom of the eighth. They needed just three more Boston outs to grab the 1986 American League pennant. Witt was coming out for the ninth. He had thrown 106 pitches to this point in the game. The first man he would see was Bill Buckner. The venerable Buckner hit a ground ball through the infield into centre field. Immediately, Dave Stapleton came out to pinch run for him.

Big Jim Rice was the next batter. Witt got him looking at strike three on just three tosses. Then it was Don Baylor’s turn to step in. He liked to crowd the plate and Witt was trying to be careful with the big man. The count went full and on the sixth pitch of the at bat, Baylor deposited Witt’s delivery over the left field wall. We now had a one-run ballgame. The tension was eased slightly when Witt got Dwight Evans to pop up to DeCinces at third.

That brought Rich Gedman up to the plate with two out. Gedman had banged out a home run, a double and a single in this game and Mauch didn’t want Witt to have to face him again. He had the lefty Gary Lucas warming up in the bullpen just for this situation. Lucas had faced Gedman twice in his career and had struck the Sox’ catcher out both times. That was a nice stat, but on Lucas’ first pitch, he came in too tight on Gedman and hit him on the hand, putting him on first.

After the game, Mauch told reporters that he might have used Witt in this situation if Gedman hadn’t hammered him all night to that point. “I can handle this, but if I let him pitch to Gedman again and he hangs out another rope, that I couldn’t handle. I had seen Gedman take enough hacks off Witt for one day, and I had never seen Gedman do anything but strike out against Lucas. I mean, if Lucas lost him, he wasn’t going to lose him big, and then I’ve got my big man (Moore) for the other guy (Dave Henderson).”

In 1986, Moore had still been the team’s closer, but he had been dealing with persistent soreness in his pitching shoulder and his rib cage. That curtailed his usefulness and his effectiveness. Nonetheless, this was his time. Was he hurting before and during this game? Mauch told the press that Moore wouldn’t have told him if he was. Moore was a competitor, and he relished these situations.

So, Moore came in to face Henderson with Gedman on first and the game on the line. He got the count to two balls and two strikes. Then he threw a fastball that Henderson fouled off. Same on the next pitch. The count was still 2-and-2. Moore then threw a splitter that didn’t drop. Henderson pounded it out for a home run. The game was suddenly very different. Boston was now leading 6-5 as the teams went into the bottom of the ninth.

After the game, someone asked Moore about that pitch and whether it was a function of the pain he’s suffered all season. “I can’t blame my arm,” Moore told the reporter. “My pitch selection was bad. I was throwing fastballs, and he was fouling them off, so I went with my split-finger. I thought maybe I’d catch him off guard, but it was right in his swing. I really shouldn’t have thrown him an off-speed pitch, because that’s the kind of bat speed he has. I should have stayed with the hard stuff. I wanted it down in the dirt. I wanted to bounce the split-finger to him.”

The Angels were down, but the game wasn’t over. Yet.

Bob Stanley was still in the game for Boston in the bottom of the ninth and he allowed Bob Boone to line a pitch into left field to open the inning. Boone was on first. Mauch sent Ruppert Jones in to pinch run for his catcher. Gary Pettis got the bunt sign, and he laid a successful sacrifice down the first base line to move Jones up ninety feet. That was all for Stanley and Boston manager John McNamara brought Joe Sambito in to pitch to Rob Wilfong.

Wilfong went up there hacking and he smacked the first pitch he saw from Sambito through the right side of the infield. That brought Jones home and tied the game. The Angels could still potentially win this game and this series today. Sambito then got the hook and McNamara brought in Steve Crawford to face Dick Schofield.

Schofield pounded a grounder through the same hole in the right side that Wilfong did. Wilfong ended up on third. When Brian Downing got ahead in the count, the Sox elected to intentionally walk him to load the bases. Doug DeCinces then hit Crawford’s first pitch in the air to right field, but it wasn’t deep enough to bring Wilfong home. It was now down to Bobby Grich. He lined a 2-2 pitch right at Crawford, and the Boston righty managed to snag it for the third out of the inning.

The score was tied 6-6 after nine full innings. We were going to extras.

Moore was still out there for the tenth and the first man he saw was Wade Boggs. He missed the zone on a 3-and-1 pitch to walk the great Boston hitter. But then he got Marty Barrett to hit into a fielders’ choice and Boggs was retired at second. After a Dave Stapleton single to right moved Barrett around to third, Moore caught Jim Rice first-pitch swinging and got him to hit into a 6-4-3 double play to end the inning.

The first man up for the Angels in the bottom of the tenth was Reggie Jackson. He was facing Crawford. The count went full before Jackson hit a grounder to Barrett at second for the first out. Then Devon White went down swinging. Jerry Narron had replaced Bob Boone at catcher and he was issued a four-pitch walk. But the inning ended when Gary Pettis lofted a fly ball to left that was caught by Rice.

Moore was back out for the Red Sox’ eleventh inning. The first man up was Don Baylor. On the third pitch of the at bat, Moore came inside a little too close and plunked the big man. “He (Baylor) was up on the plate, and I was trying to throw a running fastball in on his hands. That’s how you get him out. But I started it out too far inside. My control hasn’t been really too good lately. Most of the year, I haven’t really been happy with my control.”

Moore’s problems were compounded when he gave up a single to Dwight Evans right after that. There were now runners on first and second. Rich Gedman then laid down a perfect bunt and reached first to load the bases. The next batter was the man who homered off Moore back in the ninth, Dave Henderson. He hit a fly ball to centre that was caught but it was deep enough to bring Baylor home with the go-ahead run. The score was now 7-6 for Boston. That was how it would end.

Donnie Moore had been the hero for the Angels in 1985, but after his performance in Anaheim in Game Five, he had been booed mercilessly as he left the field. “They pay their money, and they can do what they want. That’s a part of the game. I’ve been this way before. Anyone can stand in front of the cameras and take the success.”

“My job’s not an easy job. I gotta make the pitches. When you’re bad, you’re bad. I can handle bad. I’ve had a roller-coaster career. Things have never come easy for me. I can handle it. I’m down now, but when I’m out there Tuesday, I’ll be up. I have to be ready by Tuesday.”

Moore could sound brave in front of the microphones and notepads, but that loss did crush him. Pitching coach Marcel Lachemann had a long talk with Moore to console him after he gave up that home run to Henderson.

The teams would go back to Fenway Park for Game Six. But the loss in the fifth game was like an emotional dagger to the hearts of the 1986 California Angels. They jumped out to a 2-0 lead in the first inning of the sixth game. But right after, in the bottom of the first, the Red Sox would tie the game. The Angels would never have a lead in a game in this series again. They lost that sixth game 10-4 and they were never in Game Seven, losing it 8-1.

The Red Sox would go on to play the New York Mets in the 1986 World Series. That was a classic and we all know how it ended.

* * *

That loss in the fifth game didn’t just derail the Angels in 1986. The following year, they were terrible. They finished at 75-87 and in sixth place in the AL West in 1987. Gene Mauch made it to the end of that season and then was replaced by Cookie Rojas. The following year, they put up the same record and ended up in fourth. Rojas didn’t make it to the end of the season.

For Donnie Moore, his career went downward gradually over the 1987 and 1988 seasons. The booing of the Angels’ fans never stopped. During the 1987 campaign, he lost his closer’s role to DeWayne Buice. He still managed to get five saves, but his role as the big guy late in games was gone by the end of the year. In 1988, under Rojas, Moore fell out of favour and by the end of August, he had been released by the Angels.

In 1989, he signed with the Kansas City Royals. He never played with the big club. He spent whatever baseball time he had with Omaha in Triple-A. On June 12, the Royals released him. He felt like he had been cut adrift, without baseball in his life for the first time. He didn’t know how to deal with that loss. He fell into a spiral of depression. According to Mark Kreidler in an ESPN piece on the eve of the 2002 World Series, which featured the now-Anaheim Angels and the San Francisco Giants, he cited several sources who said that Moore was also battling substance-abuse.

Moore’s marriage and relationship with his wife, Tonya, was, according to Kreidler, ‘complicated and sometimes abusive’. On July 18, 1989, Tonya and Donnie engaged in an argument in their Anaheim Hills home. Donnie pulled out a gun and shot Tonya three times. Tonya and their 17-year-old Demetria took off. Demetria drove Tonya to the hospital. She survived. But Donnie, with one of their sons still in the house, shot and killed himself.

* * *

Hubie Brooks was catatonic when he got the news from his mother. Wallace Johnson spoke to the Los Angeles Times’ Bill Plaschke about his then teammate. “He (Hubie) came out after the phone call like he was in another world. He said, ‘Donnie is dead.’ Then he didn’t say anything else. And we knew he was hurting. We didn’t know how long he would be gone.”

It turned out that Hubie wouldn’t be gone. He stayed with his teammates and played the games. With a heavy heart undoubtedly, but he stayed and played. “The man persevered,” Johnson told Plaschke. “Unbelievably persevered. Never said anything about the death the first day. Just went out and played.”

But how? Why? Why would he not take some kind of an emotional break? “It ain’t my style not to play,” Brooks told the Los Angeles Times writer. “It ain’t my style not to want to be out there when it counts. Donnie always told me, ‘You can make it. You can do it.’ More than ever, when he died, I wanted to be out there.”

Brooks explained to Plaschke how he and Moore were so close. “Donnie was my mother’s brother’s kid. But because we used to visit them so much down in Texas, we became like brothers. Losing him, that’s what it was like. It was like losing a brother.” Brooks continued. “I ain’t done dealing with it yet. My whole family has to come to grips with it. It will be there the remainder of my life. You think about him, and you think, ‘Damn, man, why?’ What was going through his head? Why didn’t he give any of us a sign? What was he trying to tell us? The worst part is, he’s not here to give us any answers.”

At the time he got the call from his mother, Brooks began to try to figure out what he should do. His team was in first place in the NL East and, after he learned about the arrangements, he thought that the best thing was to stay and play with his team. “That first five or six days, it was so rough, but I realized, I got to keep playing. I do everybody the most good on the field. I go crazy if I don’t play. I got to play.”

As often happens when someone goes through a seismic sadness, Brooks channeled all his focus on something else. He dove deep into playing baseball, and he found himself playing the best ball of his season. “It was strange, but once on that field, I could only think about baseball. It actually helped my powers of concentration. When I went home at night, it was different. The memories of Donnie all came back to me again. But when I went out the next day, at least during the game, the hurt feelings were gone.”

By the end of July, the Expos were still in first place in the NL East. Their lead over Chicago was down to just two games. But by mid-August, the Cubs and the Mets had passed them by. The 1989 season ended with the Expos at an even .500 at 81-81. They ended up fourth in their division. After the season, Hubie Brooks would go home and play with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1990.

* * *

The day after Moore shot his wife and killed himself, Elliott Almond and Mike Penner wrote a piece in the Los Angeles Times explaining how Moore never mentally or emotionally got past that pitch to Dave Henderson that resulted in a home run back in 1986. They talked to a number of people including his former manager Mauch, teammates, friends and his agent for twelve years, Dave Pinter.

“Ever since he gave up the home run to Dave Henderson, he was never himself again,” Pinter told Almond and Penner. “He blamed himself for the Angels not going to the World Series. He constantly talked about the Henderson home run. It was that important to him that the Angels make it to the World Series. He couldn’t get over it.”

Pinter continued, “I tried to get him to go to a psychiatrist, but he said, ‘I don’t need it. I’ll get over it.’ Even when he was told that one pitch doesn’t make a season, he couldn’t get over it. That home run killed him.”

Brian Downing played in the majors from 1973 to 1992. He joined the Angels in 1978 and played in Anaheim until the end of the 1990 season. He was a catcher, left fielder and designated hitter while with the team. He threw a lot of the blame for Moore’s depression at the media. “Everything revolved around one…pitch. You destroyed a man’s life over one pitch. The guy was just not the same after that. You buried the guy. He was never treated fairly. He wasn’t given the credit for all the good things he did.”

Downing contended that the endless booing that Moore endured because of the treatment he received from the media. “Nobody was sympathetic. It was always, ‘He’s jaking it. He’s fooling around.’ He was a very sensitive guy. I never ever saw the guy credited for getting us to the playoffs, because all you ever heard about, all you ever read about was one…pitch.”

Doug DeCinces played third base on that Angels team from 1982 to 1987. Before that, he was a Baltimore Oriole from 1973 to 1981. He was a little more measured but concurred with Downing. “I think it is highly unfortunate that most fans will remember one pitch about Donnie. I would have hoped Don would have forgotten that pitch.”

DeCinces went on, “What most people don’t realize is that his arm was hurt in that situation, but because of his fierce competitiveness, he took the ball, knowing that he was hurt. Still, he was going to give it everything he had.”

Through the 1987 season, Moore was dealing with issues in his shoulder and his rib cage. He would spend time through the season on the disabled list. The team was in the thick of the division race that year, but Moore was unable to participate for periods of time because of his injuries. Mike Port was the team’s general manager, and he attacked Moore, hinting that his reliever was “a malingerer” and basically telling him to “get out there and pitch.”

In the ensuing off-season, it was determined that he had been trying to pitch with a bone spur in his lower spine. The spur was surgically removed, and the hope was that the old Donnie Moore would return. When he didn’t, there was more frustration, more time on the DL, more negativity and more booing.

Downing talked about the nature of the role of a closer. “That has to be a tough job, going from on top of the world one day to the bottom in a split second. Unfortunately, he never got back to the top of the box. He always said to me, ‘they (the booing) don’t bother me’, but he put up a big façade. He was a tough guy, but I can’t believe it didn’t bother him.”

Wally Joyner had entered the Angels lineup in 1986 at first base and became an immediate All-Star. He saw what had been going on with his teammate and closer. “I know he was obviously frustrated. I’m sure it was hard on him. It was hard for me to watch that happen to Donnie. You don’t wish that on anybody, especially one of your teammates.”

Gene Mauch said that it was because of Moore that the team even contended in 1985 and 1986. “He made our 1985 season. He saved 31 games that year. That was something we needed desperately. He singlehandedly made our season. If he had been in a little better shape at the end of the 1986 season, that would have perhaps made his life different. If his arm had been a little better… The man had a lot of courage and a lot of heart.”

* * *

When the Angels made it to the World Series in 2002, there was a lot of revisiting of Donnie Moore and his pitch to Dave Henderson and the way he ended his life. Was it the pitch to Henderson that caused Moore to carry the pain with him for the remainder of his life? Or was it something more complicated and perhaps more insidious.

In a column in the Austin American-Statesman, Brad Parks contended that there was a deeper and perhaps longer seated reason that it all unfolded the way it did. Parks sought out people in Moore’s life who knew him well to try to unravel the ball of yarn that was Donnie Moore.

Where Moore’s agent, Dave Pinter, felt that his client was consumed with the home run that Henderson hit in 1986, Moore’s close friend and one-time lawyer, Randall Johnson, held a different opinion. “Let me ask you something. If you were really still troubled about one pitch, if that’s really what was haunting you, why would you shoot your wife?” Johnson went on. “Because it didn’t have anything to do with the pitch.”

Reggie Jackson was the designated hitter on that fateful day back in 1986 and he agreed with Johnson. “It’s become a great story that people tell. Donnie Moore killed himself because of one pitch to Dave Henderson. But it’s just a story. I don’t believe it for a moment. I never heard that from Donnie. I never heard him talk about Dave Henderson.”

Indeed, according to Parks, Moore’s troubles went a lot farther than one pitch in the fall of 1986. And according to Jackson, those troubles were problems with money, problems in his marriage and trying to deal with a life that didn’t include playing baseball.

In fact, the night before the tragic shooting, Moore and Jackson spoke. There were reports that Moore asked Jackson for $10,000. “It was a lot more than $10,000,” Jackson told Parks. “If it was $10,000, I would have given it to him in a heartbeat.” Jackson wracked his brain about that conversation. “I’ve second-guessed myself a lot about that. What if I had given him the money? Would it have made a difference?”

Moore’s lawyer, Johnson, told Parks that Moore had signed a three-year, $3 million contract back in 1985. Despite that, Moore had no savings or real investments. He had a mortgage on an $850,000 home, “three kids, a taste for gambling, an eye for nice clothes and little sense of fiscal restraint.”

When Moore was in Omaha in 1989, he was an old guy among a bunch of young kids who wanted to climb the ladder to the big leagues. Also on that team was Bill Laskey, another guy in his 30s who was also trying to hold on to that dream of playing in the majors. The two men became good friends. They would often talk, and they roomed together on the road. Laskey mentioned to Parks how Moore always had a wad of cash on him.

“He always had a roll of hundred-dollar bills with him. And he would spend it like there was no tomorrow. I don’t think he cared what he lost.”

When it came to his family though, Moore always seemed very detached. Neither Moore nor Laskey had their wives with them while playing for Omaha. And while Laskey would spend a lot of his spare time on the phone talking with his wife and his kids, for Moore it was the opposite.

“He checked in, that’s all he did” Laskey told Parks. “His conversations were five, ten, fifteen minutes at most. He was a very warm and friendly guy and a really good dude, but he could be very cold when it came to his family. He had a lot of problems with his wife.”

Donnie and Tonya had a bunch of issues they disagreed on. He wanted to move the family back to Lubbock, Texas. She wanted to stay in California. With their kids now older teenagers, she wanted to go out at night. He didn’t like that. For a while, Tonya had wanted Donnie to retire from baseball. He felt that there was still a place in the game for him.

When Moore was released from the Royals in June, it was Laskey who drove him to the airport. A little over a month later, on that fateful day, July 18, 1989, Donnie and Tonya were having an argument about the house. It became heated. At approximately 4:30 that afternoon, Donnie went into the bedroom. In the closet, he had a .45-calibre handgun. It had seven bullets in it.

Moore walked back into the kitchen and pointed the gun at Tonya. He had known her since high school. They had been sweethearts. They had three children together. He fired one shot at her. She ran back into the laundry room. He chased after her and fired off four more rounds. Three of the bullets had hit her. She’d been struck in the neck, lung and liver.

She struggled to make it into the garage. Her daughter, Demetria, got her into the car and drove her to the hospital. Tonya survived. The type of bullets in the gun were the reason she was able to survive, according to Johnson. “The kind of rounds he had loaded in the gun were for duck hunting. They’re designed to go straight through the duck instead of exploding the duck on impact. So, the bullets went straight through her.”

Moore went back into the kitchen. He knew he had two bullets left. He fired once. He was gone.

Johnson has no doubt that the home run had no bearing on his reason to end his own life. “I have no question he only killed himself because he thought he had killed his wife and then came to his senses and said, ‘Oh my god, look at what I’ve done.’”

* * *

Tonya Moore eventually remarried, and it’s reported that she has relocated. She did do an interview with GQ Magazine a few months after that day in July of 1989. She told her interviewer that her husband used to beat her and that he “was no angel.”

* * *

It’s a terribly sad story and one that is not as simple as some might paint it. Randall Johnson summed it up well in Brad Parks’ column in the American-Statesman. “The fact is, Donnie had a whole plethora of problems, the very least of which was that pitch.”

* * *

Howie’s latest book MORE Crazy Days & Wild Nights, eleven new stories of outlandish and wild events that occurred in sports over the last fifty years,is available on Amazon. It’s the follow-up to his first book of 2023, Crazy Days & Wild Nights! If you love sports and sports history, you need these books!

And watch for Howie’s latest book, The Consequences of Chance, to come out November 1 on Amazon!

You can hear Howie, and his co-host Shawn Lavigne talk sports history on The Sports Lunatics Show, a sports history podcast, on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, iHeart Radio, TuneIn Radio and Google Podcasts and at firedupnetwork.ca on 212 different platforms. Check out The Sports Lunatics Show on YouTube too! Please like and subscribe so others can find their shows more easily after you. And check out all their great content at thesportslunatics.com.

The Sports Lunatics Show can now also be heard on Sundays at noon on CKDJ 107.9FM in Ottawa or online at ckdj.net .