by Howie Mooney

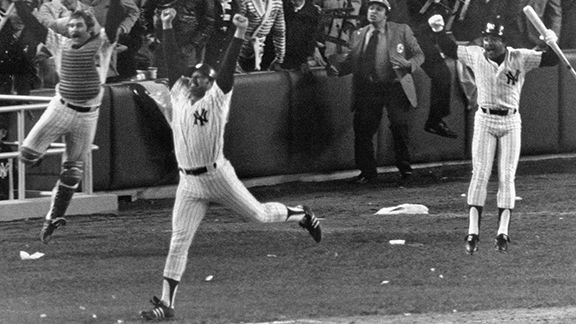

The Cincinnati Reds had barely left the Yankee Stadium field after sweeping the Bronx Bombers in the 1976 World Series and the statements about this team’s place in history were already being made and pondered. “History will prove this is one of the greatest clubs ever put together,” Reds’ manager Sparky Anderson declared to whomever would listen in the celebrations of the visitors’ club house after the game.

“This is the first time a National League team has won the World Series back-to-back in 54 years. It may be another 54 years before anybody does it again,” said Pete Rose to the numerous members of the press when it was all over.

Joe Morgan had a more elongated response about the quality of his team. “If I had to explain our success in a word, it would be ‘discipline’. This is a hard-disciplined club. You have to conform, or you don’t stay. You must place the success of the team above your own personal ambitions. Indeed, that may be our biggest asset – being a team instead of individuals.”

When it came to what he saw for the immediate future, Morgan was again optimistic. “We should make it three in a row next year. I can’t see anybody beating us. This is the best team I’ve ever seen in the big leagues. It has everything – speed, hitting, defense, the long ball. And pitching too. Our pitching staff is underrated.”

Al DeSantis was a staff sportswriter for the Middletown (N.Y.) Times Herald Record when he covered this World Series. He was 62 years old as he stood in the Reds room after that 1976 October classic. He had covered his first World Series in 1944 when both teams hailed from St. Louis. The Browns and Cardinals faced each other. Every game was at Sportsman’s Park and each team could sleep at home through the entire affair.

In his column immediately following the final out of the final game of the 1976 series, DeSantis called this edition of the Reds the greatest team he had ever laid eyes on. Since that 1944 October Classic, DeSantis wrote, “I’ve covered most of them since, including coverage this week of the best team I ever saw, the Cincinnati Reds, an incredibly talented club that ground the New York Yankees into dust in four games.”

He continued, “There were great Yankee teams and great Dodger Teams and great Cardinal teams after that ’44 debut, but none, man to man, measured up to these Reds of 1976. It tells you something about Red power when a .307 hitter over the regular season, Cesar Geronimo, bats eighth.”

For most of that seven-year window from 1970 to 1976, this Reds team was the measuring stick in baseball. Certainly, in the previous two seasons, 1975 and 1976, they were the best of the best. They were also the team with the biggest target on their backs and every other team looked to bring their best efforts when they were going to face Cincinnati.

In the joy of that club house on that day, there was only the camaraderie that envelops champions. There’s an old quote that is credited to the great Philadelphia Flyers’ coach of the 1970s, Fred Shero, that goes “Win together today and we’ll walk together forever.” Certainly, there is a tremendous amount of truth to that saying, and no one in that champagne-soaked room on that day was ever thinking about saying goodbye to any of their teammates. Not even for a second.

But change in sports – and in life – is inevitable and there would surely by some kind of movement in the Reds’ roster as the calendar shifted from 1976 to 1977. The first change that the team would see was one that was probably inevitable. Don Gullett’s contract had expired as the 1976 season ended and he was set to be granted the right of free agency.

Free agency was still a relatively new thing in baseball in 1976 and it was one that seemed to appal Sparky Anderson. “I don’t want to lose Gullett. I don’t want to lose any member of this club. This is a class club, but if these guys place money before everything else, we’re a pretty sick society.” ‘Sick society’ or not, it was a right fairly earned and why wouldn’t a player want to make the most they possibly could if they were good enough?

Just as sure as God made little green apples, Gullett became a free agent on November 1 and was able to entertain offers from any team that wanted his services. In mid November, he made his choice and on November 18, it was announced that he had signed a six-year contract with the team his Reds had beaten in the World Series, the New York Yankees.

The 25-year-old Gullett, his agent, Jerry Kapstein (the Scott Boras of his day, perhaps), Yankees owner George Steinbrenner and team president Gabe Paul were all together in New York to make the announcement. “We feel he’s a modern Whitey Ford,” Paul told the assembled reporters. Gullett compiled a record of 26-8 over the span of the 1975 and 1976 seasons and a 91-44 mark over his seven National League campaigns.

Gullett appeared to be genuinely enthused about the deal. “I’m so excited. I don’t know what to say. This is a winning team with a great background, and I can’t wait to start pitching for them. This club was more interested in me than the others. It’s great to be coming to a winning team like the Yankees.”

After the way they were dispatched in four straight games by the Reds, Paul and the Yankees were motivated to try to add whatever players they felt were necessary to lift their team to the level they needed to be at to win a championship. “We have been active, and we will be active,” Paul told the press. “We’ve got the wherewithal. Mr. Steinbrenner is in the room and his pockets are not depleted yet. We are anxious and willing to sign another player. We are talking to Mr. Kapstein about some of his other clients and will continue to.”

Gullett left his last start in the World Series after suffering an injury involving a tendon in his ankle. When asked about that, he answered quickly. “The ankle is fine. It feels great.” He also acknowledged that there was one big reason for his signing with his new club. “It wasn’t a hard decision for me. There’s something special behind pitching in Yankee Stadium.”

That was a bit of bad news for the Reds. But most of the team took his signing with the Yankees reasonably well. “I don’t have any hard feelings,” said Ken Griffey. “In fact, I’m happy for him. There’s nothing wrong with a guy getting security. But I think we can win it without him.” Gullett’s rotation-mate, Pat Zachry, figured that Gullett’s loss would “put a damper” on the team’s pitching depth. “We just got by without him.”

Manager Sparky Anderson wasn’t thrilled about losing one of the members of his starting rotation but thought about what Gullett, the person, meant to him. “The only thing that I hope is someday, Don will be able to look back and say he made the right decision,” thought the skipper. “I’ve always felt Don was one of the finest individuals I’ve ever met. I’ve said he’s like a son and I don’t think because of something like this that I can turn around and downgrade somebody.”

The sad news of Gullett’s leaving the team was tempered the following week when one of their best players was honoured by the league. Joe Morgan, the team’s second baseman, was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player for the second straight year. It was the first time the feat had been accomplished since Ernie Banks did it with the Chicago Cubs seventeen years earlier.

Morgan’s MVP win was the fifth in the previous seven seasons by a member of the Reds. Johnny Bench had won the league’s MVP award in 1970 and 1972. Pete Rose won it in 1973. And, of course, Morgan took the prize in 1975 and 1976. Is there anything better to illustrate the dominance the Cincinnati Reds exerted over the league in the seven-year window from 1970-76 than that?

Morgan hammered 27 homers, drove in 111 runs, batted .320, drew 114 walks and stole 60 bases. He finished ahead of his teammate George Foster in the voting and their teammate Rose finished fourth in the voting. Morgan had campaigned for Foster, and he mentioned his sadness for his teammate when talking to reporters. “As happy as I am for Joe Morgan, I am sad for George. He had a tremendous year.”

Morgan’s performances have improved every year since he had arrived in Cincinnati before the 1972 season. He made sure he gave credit to his batting coach. “Ted Kluszewski gets as much credit for this as I do. Ted worked with me from the start. I told him, ‘I’m not afraid of work.’ And we got immediate results,” Morgan told reporters.

Morgan was widely regarded as the best player in baseball in 1976. The Reds were the game’s best team. And with free agency now on the horizon, there was a lot of speculation as to the role that money would now play in trying to keep this extremely talented group together moving forward. Early in November of 1976, Earl Lawson wrote in a Cincinnati Post piece, about that very subject.

With contract values sure to rise in the very near future for players around the league, how would general manager Bob Howsam be able to juggle the books in order to keep the band together? According to Lawson, Morgan and Johnny Bench were set to make over $200,000 each in 1977. Morgan was said to be eyeing an annual number at more than $300,000 as soon as he was able. Pete Rose was set to make $190,000. Tony Perez was also in that six-figure salary bracket. Surely, George Foster would be due a raise? And how about Dan Driessen after his great play in 1976?

Lawson believed that the Reds had one of the highest payrolls in baseball. Was it supposed to increase now? Among those who Lawson felt were looking for raises were Dave Concepcion, Rawly Eastwick, Will McEnaney and Ken Griffey. Griffey did not have an agent yet, nor did Driessen. But Driessen was hinting at playing out his option in 1977 and securing an agent for the time when he would most need one.

In fact, a look ahead at the contract statuses of the team showed that Morgan, Rose, Perez, Foster, Griffey, Driessen, Jack Billingham, Pat Zachry and Fred Norman all had contracts that were set to expire after the 1977 season. This was the financial upheaval that Howsam and the Reds – indeed every team in baseball – was beginning to face as the game began to move forward in this new era of free agency.

Driessen was a guy whom Anderson wanted to see play more often, especially given the way he showed that he could handle a bat in the postseason. But who moves out of the lineup to give him more playing time. Pretty much the only way to give Driessen that time would be to sit or possibly trade the 34-year-old (going on 35) Tony Perez. Was that a subject that could even be conceivable? The idea was being talked about in the media. In fact, the notion had been discussed quietly over the previous couple of seasons but was always quickly brushed away.

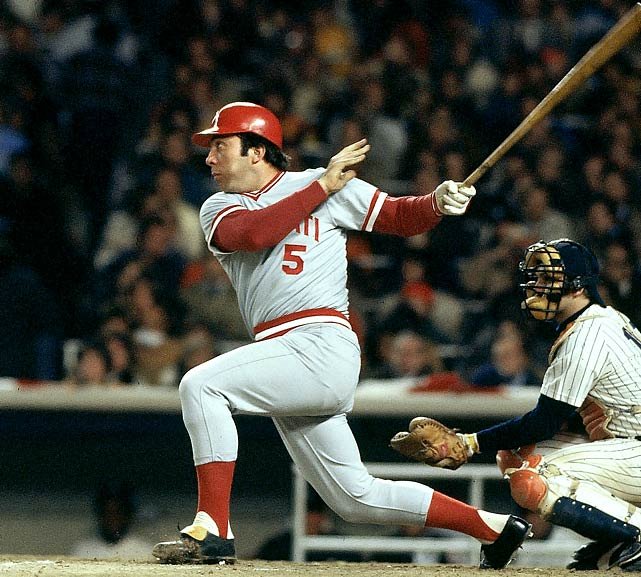

Lawson mentioned the idea in his piece. In early November the idea was brought up to Pete Rose and he sounded strongly against it. “Tony Perez is my best friend in baseball. We’ve played together since 1960 – from the day I was a week out of high school, and he was two weeks out of Cuba. There’s a lot about Tony Perez you have to read between the lines.”

Rose continued,” He is like a father to Dave Concepcion. The white players look up to me and Johnny Bench. The black players look up to Joe Morgan. The Spanish players look up to Tony Perez. I would never trade Perez. He is an awesome individual. I like Dan Driessen too. My wife introduced Danny to his wife. I just don’t want to find out what the Reds would be like without Tony Perez. I want us to retire together in Cincinnati.”

The subject of moving Perez seemed to be one of those nagging things in Cincinnati in November of 1976 – much like an itch in a place you can’t reach. Fans were weighing in as well. Mrs. G. Cox wrote the Cincinnati Post saying, “(I)f they let Tony go, we aren’t going to be too eager to care (about the Reds anymore). Tony has been the best first baseman we have ever had. Better keep him.”

Nancy Marsh wrote the paper to say, “I’m another Tony Perez fan and I just can’t understand how the Reds can even think of trading him. I, for one, wouldn’t care to see another game (no offense to the other players) because it wouldn’t be the same without Tony in the lineup. So come on all you Perez fans, let’s here (sic) it for him before it’s too late.”

When you look at Perez’ stats over the period from 1970-76 and see what he had given his club, you see the production and understand why he was so revered within the club house and in the city. He had been an All-Star four times in that span and in every one of the previous three seasons. Over a ten-year window from 1967-76, he was an All-Star seven times and had driven in at least 90 runs every year – six of those seasons saw him with more than 100 RBIs.

Perez was one of those ‘heart-and-soul’ guys who is essential to a strong team culture. The problem for the Reds was that they had a bunch of ‘heart-and-soul’ guys who were on expiring contracts, and they had a question about being able to afford to keep them all. And they had young guys who needed and deserved playing time as well.

Dave Anderson, the long-established writer for the New York Times, wrote in a late-November piece that with an important left-hander like Don Gullett now gone, the Reds might have to look at trading Perez to get a suitable replacement for their former ace. That would also allow them to give Driessen more playing time. But in doing that, would the Reds continue to be the force they had been over the last seven years? Likely not.

What had begun as a slow roll had evolved into a steady rumble. As November turned into December, the talk about possibly trading Perez seemed to turn into a discussion of where they should send him. There was also a lot of talk against the move. But there was an increasing feeling that something would be done that involved moving ‘The Big Dog’.

In the Tuesday, December 7 Cincinnati Enquirer, Bob Hertzel had an article discussing the notion of trading Perez to Philadelphia for right-hander Jim Lonborg. He also posited that Perez could be sent to the Chicago Cubs for Bill Bonham. Bonham was also a righty. Hertzel figured that the Phils could use a first baseman, what with Dick Allen going to Oakland. Philly also had a ton of pitchers, if Lonborg wasn’t necessarily available.

Given the tiny configuration of Wrigley Field though, Perez might welcome a season or three hitting in Chicago. And apparently, the Cubs were also looking to deal Jose Cardenal, who happened to be a good hitter and fielder. The point seemed to be that trading Perez was no longer just a discussion point. It was now an inevitability. But that didn’t mean people had to like it.

Back to the Letters to the Editor. Lillian MacGregor wrote the Cincinnati Post a response to an earlier letter from Nancy Marsh. “I also don’t see how you can think for one minute about trading Tony Perez. It certainly would not be the same again without Tony and I will never watch or go to another baseball game without Tony. Tony is the RBI king of baseball. So, you had better keep him.”

In his December 7 piece, Bob Hertzel figured that a deal would be made by the end of that week. He was wrong about that. It actually happened on Thursday, December 16, so the following week. He wasn’t traded to Philadelphia or Chicago. But, when the news came down, it was still a surprise to many – if not a shock.

Tom Callahan was a writer for the Cincinnati Enquirer. He wrote about the story in his paper. It appeared in the December 17 edition. He found out about the trade in an unusual way. Callahan wrote, “The news came Thursday from Tony’s mailman, who telephoned that Pituka Perez (Tony’s wife) had canceled service here (in Cincinnati) next baseball season and forever. Any forwarding address? Yes. Canada.”

Before the tradehad been made public, Tony had gone for a walk. The weather was sombre, grey, and cold. People saw him. They knew who he was. They had heard all the talk and all the rumours. They all had similar words for him. “You gonna stay with us?” He knew what had already happened but couldn’t really say. All he could do was smile a shy smile and shrug his shoulders.

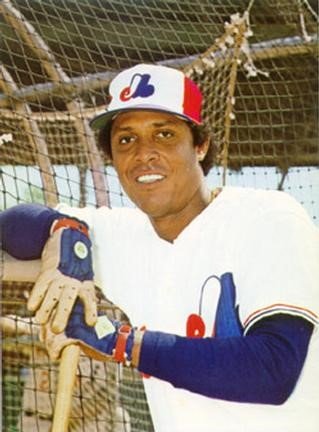

Tony Perez had been dealt in a package that went from the Cincinnati Reds to the Montreal Expos. Along with Perez, Will McEnaney went to Montreal in exchange for left-handed starting pitcher Woodie Fryman and right-handed reliever Dale Murray. The reaction in Cincinnati was one of sadness. The heart and soul of the team was no longer playing for the Cincinnati Reds.

Tony and Pituka Perez addressed reporters from the office of his lawyer, Reuven Katz, once the trade was announced. “It happened. I’m happy and I’m sad.” The look on his face though, was one of relief. Pituka sat off to the side. She was wearing a gold and diamond lock-shaped pendant around her neck. Someone asked her about it. She answered, “Tony, he is wearing the key.”

Someone asked Pituka how she felt about the trade, and she spoke from the perspective of a loving wife and partner. “Sometimes when he come home from the game, you could see in his face. He wasn’t the same happy Tony.” She saw that look of sadness, knowing he hadn’t played in the game that night.

The feeling on the Reds, with their management, was that Dan Driessen needed more repetitions at first base. But Tony didn’t say anything to reporters or to anyone really. Except to Bob Howsam. “Sometimes,” Tony told the press in Katz’ office after the trade, “I get upset. I don’t like to miss when I’m not tired. The only answer Sparky give me is ‘Danny needs a chance to play’. So, I told the Reds, finally, I love my teammates but, please, I must play every day – somewhere.”

Lee May had played first base, and he had been traded four years before to make room for Tony. Now, Tony was being traded to make way for Driessen. As someone once said, youth must be served.

Johnny Bench was there that day in Katz’ office. As he watched his friend and now former teammate talking, he was nodding in understanding of what Tony was saying. His eyes gave away the fact that he had been crying. “He totally loves people,” Bench told the Post’s Tom Callahan. At one point, Bench was called to the phone. It was Tony’s sons. “Eduardo! Victor!” Bench could be heard loudly saying into the phone. Then the catcher listened and gave the phone to someone else.

Bench looked like he was going to cry again. He told Callahan, “Eduardo wanted to know if the catcher in Montreal could hold as many baseballs as I can.” Then he broke down again, in tears.

Joe Morgan was a guy who loved Tony Perez. “Tony is a man,” Morgan had told a reporter before this day. “You want your son to be such a man.” He wasn’t there in Katz’ office but when he was reached for comment, he responded almost angrily. “Twelve years he was here. He never caused trouble. Not once. He was always loyal, and you can underline that.”

Morgan continued. “Loyal to his employer. He did his job. But it didn’t keep him here. They always used Tony Perez. They used him until they used him up.” He spoke about what Perez meant to his own development as a player as well. “He is part of what helped make me what I am. Before I came to Cincinnati, I was just Joe Morgan. Then I came here and there was Perez and Rose and Bench and they made me Joe Morgan, something special. I have to be losing a bit too.”

Tony did some reminiscing of his own as he stood in his attorney’s office. “I been thinking about my team. Johnny, Pete, Morgan. And Lee May too. Vada Pinson, Frank Robinson. Good players. I have been lucky. I hope they still win. I know they will. This is a really pro team. It knows the winning attitude.” He thought too about the leadership role he played among the Hispanic players on the Reds. “I think Davey (Concepcion), Pedro (Borbon) and Cesar (Geronimo) have matured. They don’t need me anymore. I hope not.”

“Now I will go tell it to Montreal. Give the Expos, the young players, the same attitude. And I’m glad for Driessen. But I’m not saying goodbye. Just so long,” Tony told the group there. Then he smiled and added, “I’ll be back.”

*

That day, December 16, 1976, seemed to usher a change to the baseball landscape. It wasn’t an indelible sea change that could be noticeable in an hour or a day. But over the course of a six-month baseball season, the difference could be felt. The Cincinnati Reds were no longer the Big Red Machine they had been through the previous years of the decade. They were still very good. But there was a missing element to them in 1977. And in 1978.

They had lost their soul. They had lost Tony Perez.

In 1977, the team went 88-74 and finished ten games behind the Los Angeles Dodgers in the National League West. In 1978, the Reds once again finished second in their division to those dreaded Dodgers. Their time as a machine had ended. They were now just another good ball team.

Prior to the trade, Tony Perez had played 137 games for the Reds in 1975. He played 139 games in 1976. In his first year in Montreal with the Expos, he played 154 games, and he matched his home run total of 19. He also drove in 91 runs again for the second straight year. His batting average of .283 was nothing to sneer at either. He was playing more, and he was still very productive.

Tony helped make his new team better on the field as well. Along with Perez and a new manager in Dick Williams, the Expos went from a 55-win team in 1976 to a 75-win season in 1977. The team improved each season and in 1979, the Expos finished with 95 wins but finished second that year to the Pittsburgh “We Are Family” Pirates. At the end of it all, the Bucs were just two games better than Montreal.

That Expos run that year electrified the city of Montreal and the country of Canada. They came oh, so close, but having to play 34 games and eight doubleheaders in the month of September did them in. They were tired by the last week of the season. When it was all over, manager Williams said it plainly, “I think Tony Perez is our leader on the field.” The Expos made him an offer in an attempt to keep him from going to free agency, but it wasn’t enough.

Tony’s work in Montreal though, as a player and as a mentor, all paid off as the team became a contender in the NL East for several years after that. They made the postseason in 1981, eventually losing out to the Los Angeles Dodgers and missing a trip to the World Series by the distance of a Rick Monday home run.

After that 1979 season, Tony became a free agent. He still had some baseball in him. He played three seasons in Boston with the Red Sox. He played a year in Philadelphia and then rejoined the Reds for the final three years of his career. The 1986 campaign was his last as a major leaguer. Tony Perez was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2000.

As far as the Reds were concerned, they would eventually win another World Series in 1990. They had good teams after their Big Red Machine years but nothing that closely resembling the juggernaut that they had been in 1975 and 1976. No one who ever saw those teams will ever forget the brilliance and the confidence that those Reds teams possessed. It was truly something to behold.

They were indeed The Big Red Machine.

* * *

Howie’s new book MORE Crazy Days & Wild Nights, eleven new stories of outlandish and wild events that occurred in sports over the last fifty years,is available on Amazon. It’s the follow-up to his first book of 2023, Crazy Days & Wild Nights! If you love sports and sports history, you need these books!

You can hear Howie and his co-host Shawn Lavigne talk sports history on The Sports Lunatics Show, a podcast, on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, iHeart Radio, TuneIn Radio and Google Podcasts and at firedupnetwork.ca on 212 different platforms. Check out The Sports Lunatics Show on YouTube too! Please like and subscribe so others can find the shows more easily after you. And check out all their great content at thesportslunatics.com.

The Sports Lunatics Show can now also be heard on Sundays at noon on CKDJ 107.9FM in Ottawa or online at ckdj.net .